Faizan Zaki, today, was crowned the Scripps National Spelling Bee Champion in Maryland. I found the picture of him, sprawled out on the floor, celebrating his win very endearing. After all, he has likely spent a large fraction of his 13 years cramming every word in the dictionary.

I remember first being introduced to the idea of a spelling bee when a California kid of Indian origin, Ragashree Ramachandran, won it in 1988. The article in the San Jose Mercury News had a picture of what appeared to be a shy, bespectacled kid enjoying the adulation that followed the tremendous win. For context, recall that the Indian population in America at that time was tiny (~700k or 0.28% of the US population vs 1.6% today per US Census data). So tiny that if you saw an Indian, you would walk over, introduce yourself, and almost always find a relationship less than 2.5 hops away. And, as any Indian’s win was your win, we, naturally, celebrated with her. In fact, I recall significant discussion that weekend in Joy and Ajit’s home on campus on what a spelling bee was and how one might prepare for it. We even concluded that if it had been a game in India, it would have been nailed!

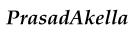

So, tracing the path from Ragashree (actually Balu Natarajan in 1985, who won it just before I arrived in the US) to Faizan, I ran some numbers. There have been 47 winners including both of them. Of the 47, 29 are of Indian origin—an astounding 62%. It gets crazier if one looks at the period from 1999, when Nupur Lala won, to today—28 out of 36 winners have been of Indian origin. 78%!! A couple of them have won on their first attempts. Curious, I dug into the details of the demographics to find that at least 8 of the 47 (17%) are from Tamil Nadu while 10 (21%) from Andhra Pradesh. And, interestingly, at least 15 (32%) come from south eastern America while only 5 (11%) come from California.

How is it that a group that represents 1.6% of America dominates? Why is it that these folks tend to be from certain parts of Southern India? What lies behind this extraordinary dominance? Since others, like me, have been curious and have dug into the question, I am going to ride on their research coattails.

The perfect storm of culture and circumstance

Researchers have discovered that it’s not a single factor but rather a convergence of cultural, linguistic, and sociological elements that creates what filmmaker Sam Rega calls a “perfect storm of events” in his 2017 video documentary, “Breaking the Bee.” The roots trace back to the 1965 Hart-Cellar Act, which opened doors for highly educated professionals from Asia. As Northwestern anthropologist Shalini Shankar notes, this immigration policy specifically sought scientists, engineers, and medical professionals—creating a community where 79.5% of Indian immigrants hold bachelor’s degrees or higher, compared to just 32.2% of U.S.-born Americans.

But education levels alone don’t explain spelling prowess. The real advantage may lie deeper, in what Shankar describes as a legacy of British colonialism—the English-medium schooling system that gives Indian American parents sophisticated linguistic tools to coach their children, despite their variety of British spelling conventions. And, deeper into a culture that celebrates education, discipline, and perseverance.

Ancient memory arts meet modern competition

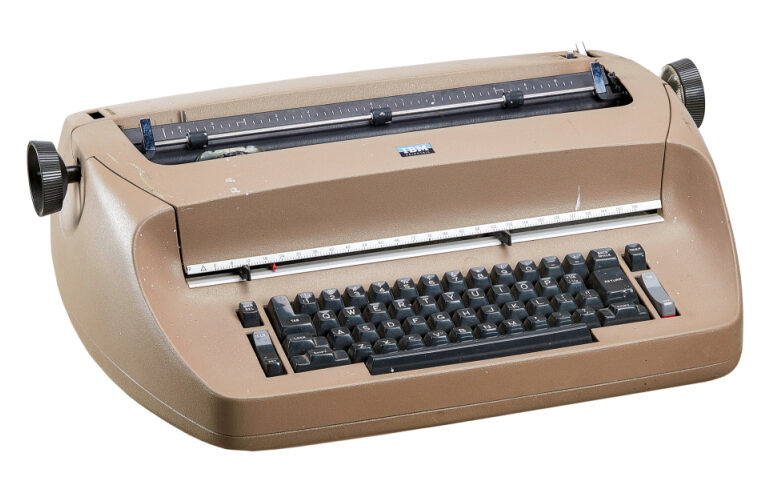

Perhaps more fascinating is the connection to India’s ancient oral tradition. Writer Gurnek Bains points to India’s development of “15 elaborate mnemonic devices” used for millennia to perfectly preserve sacred Vedic texts. UNESCO recognized this as “a masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity” in 2003.

While I didn’t go through this training as a kid, I can see the Vedic tradition of employing sophisticated memorization techniques including eleven different modes of recitation (pathas), alphabet-based mnemotechnical devices, physical movements synchronized with sounds, and visualization through hand gestures (mudras) playing out. These methods ensured word-perfect transmission across millennia, one that is manifest in a parallel Sanskrit/Bhagavad Gita chanting competition in North America even today. This cultural foundation that may (may being the operative word!) give Indian American children unique advantages in absorbing and retaining complex orthographic patterns. (My unproven hypothesis is that this is more true of the Tamilians in the group, since the level of discipline that they display in learning everything from Carnatic music to the vedas is in a league of its own.)

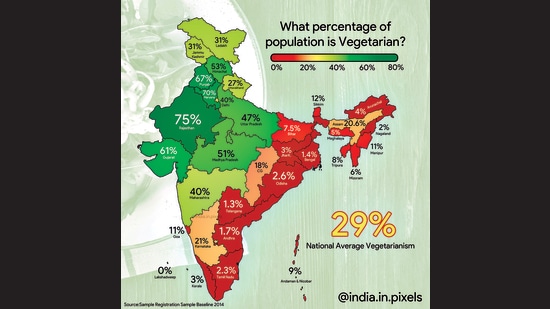

While I wasn’t surprised with the over representation of the Tamilians in the list, I will admit being surprised by the number of Andhras—as we are better known to enjoy life. I am hypothesizing that, as the chart below shows, this might simply be an artifact of the 4:1 numerical dominance of the Andhra population that followed the Y2K migration from Andhra Pradesh to the US.

The infrastructure of excellence

I was surprised to learn of the remarkable supporting infrastructure that the Indian community has built. (You now know that Chirag and Pooja were busy on soccer fields and not competing in these events!) Specialized spelling circuits like the North South Foundation and South Asian Spelling Bee create what amounts to a minor league system. The North South Foundation alone hosts competitions in 35 states with over 18,000 student participants, while the South Asian Spelling Bee has grown from 300 contestants in eight cities to over 1,000 across twelve cities. Talk of a scale that competes with soccer, football, basketball and baseball leagues!

This creates what researchers describe as intensive preparation networks where information about academic advancement is shared, generating “a generation of young Indian American intellectuals.” Unlike typical competitors who participate in just a few bees annually, Indian American children often compete multiple times against increasingly sophisticated opposition.

Family as academic enterprise

Not surprisingly, as Shalini Shankar’s ethnographic research reveals, the spelling bee preparation becomes a total family commitment and is played as a full court press. Parents—often with advanced STEM degrees—function as coaches, siblings as assistant coaches, and extended family as support systems. Some mothers quit jobs to homeschool children specifically for academic competitions. As one parent told Shankar, “We have to have 130 points above other groups” on the SAT, driving intensive after-school academic preparation.

This reflects broader patterns among Indian Americans, who have median household incomes of $119,000—well above the national median—and often invest heavily in supplemental education. Hexco Academic, a major spelling preparation company, reports that 94% of spellers advancing to Scripps finals were their customers in 2019. This will give those of us who prepared for and wrote the infamous IIT JEE (Joint Entrance Exam) a strong sense of déjà vu! Replace Hexco Academic with Agarwal’s Classes or Brilliant Tutorials and the Spelling Bee with JEE (it even rhymes!), and I can see the parents rolling over in glee. (Pardon the continued rhyming. I couldn’t help myself.)

The linguistics of advantage

The dominance isn’t, apparently, just cultural—it’s also linguistic. Children growing up in multilingual households often develop enhanced morphological and phonological awareness, crucial skills for parsing complex English words derived from Latin, Greek, and other languages. Indian American children typically know English plus their parents’ mother tongues, creating what linguists call metalinguistic advantages in understanding how languages pattern and interrelate.

As Shankar observed, it’s specifically children of professionals who become champions—not assembly line workers or cab drivers, even when they’re South Asian. The combination of high educational capital, English-medium schooling backgrounds, and cultural emphasis on academic achievement creates ideal conditions for spelling success.

Beyond the Bee

What began with Balu Natarajan’s victory in 1985 has become a cultural phenomenon that extends far beyond spelling. It represents the intersection of ancient Indian memory traditions with American competitive culture, creating what may be a uniquely successful model of immigrant achievement.

The numbers don’t lie: from Ragashree to Faizan, Indian Americans have transformed the Scripps National Spelling Bee into their own domain. But more than that, they’ve demonstrated how cultural assets—ancient memorization techniques, family commitment to education, community support networks—can be leveraged in new contexts to achieve remarkable success.

The Indian rules the American spelling bee not through any mystical “spelling gene,” but through a potent combination of cultural capital, linguistic advantages, and sheer dedicated preparation. It’s a testament both to the power of tradition and to the possibilities that emerge when ancient wisdom meets modern opportunity.

Yet, at the same time, it speaks to the imbalance that directly results from the 1965 Hart-Cellar Act—America self-selected intellectual athletes at a specific point in time. The act likely didn’t ask for sports athletes to immigrate. As we used to joke about Pooja’s encyclopedic knowledge of Bollywood (“If there was an SAT on Bollywood, Pooja will score better than 800!”), I’d close by saying that the American Indian is a spelling athlete. It comes naturally to us. Just as being a sports athlete is, unfortunately, utterly unnatural to many (most?) of us.