Strangely, I’ve been thinking about hair these last few weeks. Perhaps because I just attended two big fat Indian weddings where I was struck by the energy that went into everything from simply getting a haircut to coloring it to hiring a hairstylist to make it and the person look good!

Pondering over this, and considering my own hair, increasingly thinner and almost fully grayed, I am concluding that hair represents something fundamentally human—our endless drive for self-expression, status, cultural identity, and, at the risk of being upbraided, boosting our ego. I have, as I have since researched the topic, realized how hair has been this continuous thread (pun intended!) through human civilization, from ancient Egyptian wigs to today’s five-bladed Gillette razors and fancy Dyson hair dryers.

Hair through the ages: A visual journey

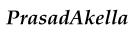

The earliest evidence of hair styling takes us back thousands of years. I’m always amazed by the sophistication of ancient civilizations—they weren’t just surviving, they were styling!

In ancient Egypt, the elite wore these elaborate wigs made from human hair and plant fibers. (Talk about high maintenance!) Meanwhile, in ancient Greece and Rome, elaborate curled styles signified who had status and wealth.

Fast forward to medieval Europe, where nobility often covered their hair completely with headdresses. Renaissance women, seeking that aristocratic look, even plucked their hairlines to create higher foreheads! (The things we do for beauty, right?)

Then came the 18th century with those towering powdered wigs that sometimes reached heights of over two feet. Can you imagine trying to sleep with that? Well, they had a solution—they actually slept sitting up! (More on that wild practice below.)

The Victorian era brought more restrained styles, though women’s updos were still intricate works of art requiring serious skill.

The 20th century? That’s when things got really interesting! We saw the bobbed hair of 1920s flappers rejecting Victorian constraints and rebelling socially post-World War I, the controlled styles of the 1950s reflecting post-war order, and the free-flowing locks of 1960s counterculture thumbing their nose at the establishment.

Gender and hair: Shared histories, different expectations

Have you ever noticed how differently we think about men’s and women’s hair? This isn’t new—it’s been baked into cultures worldwide for millennia.

For women in many cultures, long hair symbolizes femininity, fertility, and youth. The darker side? Cutting women’s hair has been used as punishment throughout history—most disturbingly seen during World War II when women accused of collaborating with enemy forces had their heads shaved publicly. And, shaving the heads of widows in India. (Both brutal reminders of how hair becomes weaponized in gender politics.)

For men, hair and especially facial hair has often signified virility, wisdom, or authority. Military regulations globally have long controlled men’s hair length. (Next time you see a military buzz cut, remember it’s a centuries-old tradition of enforced conformity!) Religious traditions bring their own rules—from Nazarite vows to uncut beards among Orthodox Jews to Sikh turbans.

Despite these differences, both men and women have used hair to signal belonging, rebellion, or conformity throughout history. Just think about the punk movement of the 1970s with mohawks and wild colors adopted by all genders, while today’s corporate culture often enforces similar standards of “professionalism” across genders. (Though I’d argue women still face far more scrutiny over their hair choices in most professional environments.)

Divine locks: Hair in religious iconography

Here’s something I’ve always found fascinating: across most major world religions, divine figures and deities are rarely depicted as bald. Think about it—have you ever seen a bald Zeus? A balding Jesus? Krishna without his peacock feather?

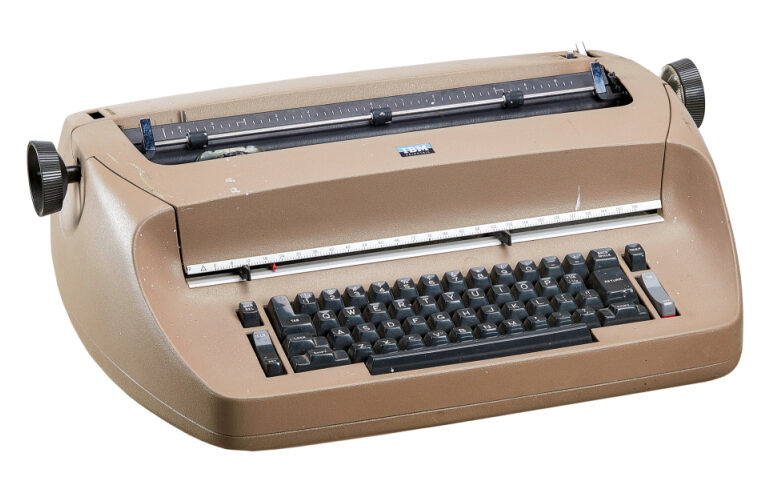

In Christian iconography, Jesus almost always has those flowing locks symbolizing his divine nature. In Hindu traditions, Shiva sports matted locks that contain the sacred Ganges, while Krishna’s hair gets the royal treatment with peacock feather adornment. The Buddha, interestingly, while often shown with a shaved head (reflecting his monastic practice), has that distinctive cranial bump called the ushnisha—technically not hair but representing enlightenment.

Greek and Roman gods? Always perfectly coiffed with full, often curled hair symbolizing eternal vigor. Even in traditions where human devotees shave their heads as a renunciation practice, the gods keep their divine locks!

The brahmin tonsure: My family’s hair history

This contrast between divine hair and human tonsure has personal significance for me. My ancestors were likely Brahmin pundits and, presumably, sages, known for their distinctive partially or fully shaved heads. Looking back, I wonder why these learned men—devoted to gods with flowing locks—deliberately removed their own hair.

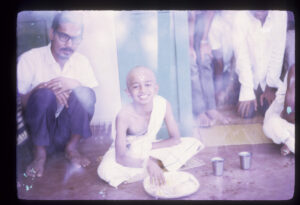

The tradition of mundana (head-shaving) in Brahmin culture fascinates me. Young Brahmin boys traditionally undergo the upanayanam ceremony as they transition to manhood, typically between ages 8-12. During this sacred ritual, their heads are shaved, leaving only the “panchashikha“—five locks of hair (four locks plus a central tuft or pigtail). This distinctive hairstyle has deep symbolic meaning, representing the five pranas (vital energies) and connecting the spiritual practitioner to the divine.

I’ve often reflected on this seeming contradiction—why would devotees shave their heads while their gods maintain luxurious locks? The answer lies in the concept of renunciation. For Brahmin sages, the partial or complete shaving of the head symbolized detachment from vanity and worldly concerns. The remaining tuft (shikha) served as a connection to the divine, a literal “thread” linking the human to the transcendent.

The historical records suggest practical reasons too—in ancient India’s hot climate, shaved heads were cooler and more hygienic, especially for those performing elaborate rituals around sacred fires. For scholars spending hours poring over texts, minimal hair maintenance meant more time for study and spiritual practice.

What I find particularly meaningful is how this tradition represents a conscious choice to distinguish the human seeker from the divine ideal—a recognition of the distance between mortal limitations and divine perfection, while still maintaining that essential connection through the symbolic shikha.

(While my own head sports a full crop of hair these days—what’s left of it, anyway!—I sometimes wonder how I would look with the traditional panchashikha of my ancestors. What I can share is what it looked like when I was all of 9!

Hair maintenance: From sitting up to dry shampoo

Remember when I mentioned 18th century French nobles sleeping sitting up? That actually happened! Those elaborate hairstyles took hours to create and were maintained for weeks or even months. During this period, bathing was infrequent (a significant understatement), and powders were used to absorb oil and mask odors. (The mental image of someone sleeping upright to protect a weeks-old hairdo powdered with scented talc to hide the smell is… something else.)

Ancient civilizations actually had some clever cleansing solutions—including natural cleansers made from clay, lye, and plants. The Romans, famously fastidious, used olive oil treatments. And contrary to popular belief, Medieval Europeans did wash their hair, though less frequently than we do, using herb-infused waters and lye soaps.

Turns out that the first commercial shampoo only appeared in the late 19th century, and daily hair washing didn’t become common until mid-20th century (largely pushed by advertising campaigns—as always, follow the money!).

Tools of the trade: The evolution of hair instruments

As an engineer, I find the evolution of hair tools particularly fascinating. Some of these implements have remained remarkably consistent in basic design for thousands of years, while others have seen revolutionary changes.

Combs are among humanity’s oldest tools, with examples dating back to 5500 BCE. Early versions were carved from bone, wood, and shell—materials readily available to ancient craftspeople. Today’s versions use plastics and metals, but the basic design remains remarkably similar. (Proof that good design endures!)

Scissors specifically designed for hair cutting appeared in ancient Egypt and Rome but didn’t reach their modern form until the 19th century when metallurgy improved enough to create truly precision cutting tools.

But razors? Those have undergone a dramatic evolution. Ancient Egyptians used sharpened copper and gold tools that I wouldn’t let anywhere near my face! Straight razors dominated for centuries until safety improvements began in the late 19th century.

Henry Nock’s invention of the Wilkinson Sword in 1772 and King Camp Gillette’s invention of the safety razor in 1901 were revolutionary—his two-bladed design made at-home shaving safer and more accessible. The innovation continued with electric razors in the 1930s and the progressive addition of blades (three, four, and finally five-bladed systems like modern Gillette razors), each promising that ever-elusive closer, more comfortable shave.

Looking back, I realize that I was fortunate to skip the open blade and two edged razor eras. How fortunate was clear when I forgot to take my 5-bladed Gillette with me to one of the weddings and I found myself falling back on a spare 2-bladed Gillette. I was struck by two observations: One, how much cleaner the shave is with the 5-bladed razor. And, second, how infrequently I nicked myself with the newer model. I can, therefore, attest there’s been genuine improvement (though I’m skeptical we need blade numbers 6, 7, or 8!) Progress, indeed!

Conclusion

When I look at the history of hair across human civilization, I’m struck by how it reflects our fundamental nature—our creativity, our social hierarchies, our technological progress, and our personal identity. From ancient Egyptian ceremonial wigs to modern five-blade razors, how we handle our hair tells us something profound about who we are.

I can’t help but wonder: what will hair historians 500 years from now say about our current practices? Will they marvel at our obsession with hair products? Will they find our styles as curious as we find powdered wigs? Or will they have moved beyond hair altogether with some gene-editing solution we can’t yet imagine? (If they have, I hope they’ve solved male pattern baldness!)

What’s your most interesting hair story or family hair tradition? I’d love to hear how hair has played a role in your life or cultural background!