Growing up in a vegetarian home in Malleswaram, Bangalore, eating at popular eateries like Kamat restaurants and MTR (Mavalli Tiffin Rooms), and despite seeing non-vegetarian dishes in other restaurants as well as sharing meals with friends who ate meat, I naively assumed that most of India was vegetarian. Little did I know that Malleswaram was one of the bastions of the Brahmin world! And, that it had colored my little world so distinctly.

More recently, when visiting with family in Delhi and looking at the food on the table — from traditional South Indian idlis to Punjabi chicken and Bengali fish, my curiosity was sparked by how this one table captured the incredible diversity of a subcontinent, each dish representing a different region, language, and way of life.

Remembering graphic descriptions in the infamous Amar Chitra Katha comics of Indian rishis/sages from Indian mythology eating everything that they could lay their hands on the one hand and of Mahavira and Gautama Buddha advocating ahimsa (non-violence) in our history classes on the other, I got more curious.

So, I delved back in time and here’s what I found.

The surprising truth about ancient India

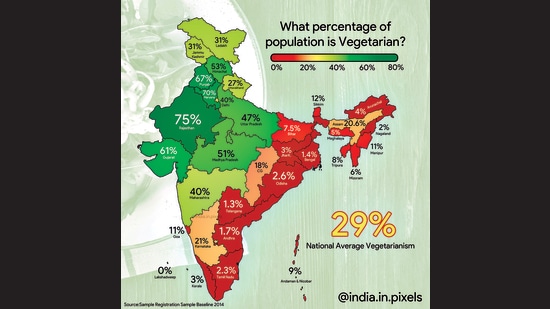

Most people assume vegetarianism is an ancient Indian tradition. The reality is far more complex and fascinating. Modern India’s vegetarian map reveals a striking pattern: while 75% of Rajasthan is vegetarian, only 3% of Tamil Nadu is! This isn’t random—it’s the result of a 3,000-year transformation driven by religion, economics, and geography.

(Source: Ashris Choudhary, 25 Jul 2020, https://x.com/indiainpixels/status/1286982097400283136)

Strikingly, and consistent with Indian mythology, ancient India was overwhelmingly meat-eating. The Rigveda, our oldest Sanskrit text, contains over 50 references to eating beef, horse, and other meats. Vedic priests regularly performed animal sacrifices and consumed the offerings. The archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley Civilization shows clear signs of cattle, buffalo, goat, and pig consumption. Even cows!

(Source: Prasad Akella, 2025, working with Claude)

The graph above, which I created working with Claude, attempts to show the move from a distinctly carnivorous diet to a little more vegetarian one as a consequence of historical events. I picked 5 milestones to do this: 1. “Ancient times” defined as pre-9th century BCE; 2. 5th century BCE to align with Mahavira and Buddha; 3. 1500 AD when the Mughals and the Europeans arrived; 4. 1900 AD when the British dominated; and 5. Current times, when the economic heft of India is dramatically changing what its population has access to and can afford to eat.

So, let’s take a walk across time…

The revolutionary 6th Century BCE and the critical role of merchants

Everything changed around the 6th century BCE with the rise of two revolutionary movements: Jainism and Buddhism.

Parshvanath (8th century BCE; 23rd Tirthankara) and later Mahavira (6th century BCE; 24th Tirthankara) established Jainism with its radical doctrine of ahimsa (non-violence). For Jains, this wasn’t just about avoiding meat—they avoided root vegetables like onions and potatoes, believing that uprooting plants caused unnecessary harm.

Around the same time, Buddha (~500 BCE) promoted compassion for all sentient beings, though early Buddhism was more flexible about diet than popular belief suggests.

But here’s the crucial insight: These religions initially appealed to merchants, not the general population.

Why merchants? Goes back to my previous articles on the power of social networks! (Relationships matter, Why is Paul Revere revered?) Unlike Judaism and Hinduism which were primarily ethno-religious traditions that were typically transmitted through birth and community belonging, religions like Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, which grew by active proselytization, initially found their strongest footing among merchant communities for several interconnected reasons:

- Economic networks and mobility: Merchants traveled extensively along trade routes, creating natural channels for religious ideas to spread. They needed portable belief systems that could travel with them across different kingdoms and cultures, rather than being tied to specific local temples or rituals.

- Cosmopolitan worldview: Trading required merchants to interact with diverse peoples and navigate different cultural systems. Religions that emphasized universal principles (like salvation, compassion, or submission to one God) were more appealing than highly localized, ethnic traditions that might not translate across borders.

- Social mobility and status: Merchants often occupied an ambiguous social position—wealthy but not necessarily high-born. New religions frequently offered alternative paths to spiritual prestige that didn’t depend on traditional aristocratic or priestly hierarchies. Early Christianity, for instance, appealed to those seeking dignity outside the Roman class system.

- Practical advantages: Religious networks provided trust, common ethical frameworks, and even financial services across vast distances. A Christian merchant in Alexandria could trust a Christian merchant in Antioch partly because they shared moral codes and community bonds.

- Urban concentration: Merchants clustered in cities and trading posts, creating the population density needed for new religious movements to take root and grow, whereas rural populations remained more tied to ancestral traditions.

The business of non-violence

Why would traders embrace vegetarianism? The answer lies in practical business considerations:

The Jain merchant advantage

Jainism found its strongest foothold among trading communities in western India—modern-day Gujarat and Rajasthan. The Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions created extensive merchant networks that prioritized:

- Trust and reputation in business dealings

- Non-violent conflict resolution essential for trade

- Strict dietary discipline that demonstrated self-control

- Community solidarity through shared practices

The Baniya transformation

The term “Baniya” comes from Sanskrit vaṇija (trader). These merchant castes—including Agarwals, Oswals, and Maheshwaris—gradually adopted vegetarianism for multiple reasons:

- Religious influence: Many became Jains or Vaishnava Hindus

- An unusual example of extreme vegetarianism among the Vaishnava Hindus is the Bishnoi community which, starting in about 1500 AD, follows 29 (Bishnoi = portmanteau of “bis” (= twenty) and “noi” (= nine) principles. And, in doing so, is very firmly vegetarian—they won’t eat anything that involves killing—no meat, fish, or even honey (since taking honey harms bees). They also avoid eating after sunset to prevent accidentally consuming insects.

- Business networks: Vegetarian merchants could eat together and build trust

- Social mobility: Dietary restrictions elevated their status

- Risk management: Avoiding conflicts over food practices in diverse trading environments

The brahmin counter-revolution

Faced with the growing influence of Jainism and Buddhism, Brahmin priests made a strategic pivot. By the early centuries CE, many Brahmin communities abandoned their traditional meat-eating and animal sacrifice to:

- Reclaim moral authority from Buddhist and Jain competitors

- Adopt the superior virtue of non-violence

- Maintain their position as spiritual leaders

This wasn’t universal—many Brahmin communities, especially in eastern India and Kashmir, continued eating meat and fish well into the medieval period.

The geographic revolution: Why South India stayed non-vegetarian

The most fascinating aspect of this story is regional variation—to be candid, I was shocked to see that under 3% of the southern states are vegetarian. So, how is it that northwestern India embraced vegetarianism while southern and eastern India largely resisted it?

The maritime merchant story

Consider the Nattukottai Chettiars of Tamil Nadu—one of India’s most successful merchant communities. Initially vegetarian, they completely transformed their diet through international trade:

“The Chettiars have traditionally been vegetarians. Their feasts at lifestyle ritual functions remain vegetarian. But trade once had them criss-crossing the southern reaches of peninsular India and absorbing non-vegetarian influences from the Malabar Coast… Further non-vegetarian influences became entrenched in Chettiar food habits from the late 18th Century after they established businesses in Ceylon, Burma, the Dutch East Indies, French Indo-China and what is now Malaysia and Singapore.” [Nair & Meyyappan, 2014]

Different business environments

Northern merchants traded primarily within India’s Hindu-Jain-Buddhist cultural sphere, where vegetarianism provided social advantages.

Southern merchants engaged in maritime trade with Southeast Asia, dealing with Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim populations who were non-vegetarian. Dietary flexibility became essential for business success.

The lactose tolerance factor

Putzing around, I chanced upon recent research that suggests another fascinating dimension: genetic differences in lactose tolerance. Northwestern Indians have higher rates of adult lactose tolerance, allowing them to substitute dairy for meat as a protein source. Southern and eastern populations, with lower lactose tolerance, relied more heavily on fish and meat for nutrition. (I don’t fully grok this. So, if you do, please let me know!)

The colonial crystallization

The British period (1757-1947) crystallized these regional patterns. Colonial administrators conducted extensive surveys and censuses, creating fixed categories of “vegetarian” and “non-vegetarian” communities. The railway system spread Gujarati and Rajasthani traders across India, but their dietary practices remained geographically concentrated.

Ironically, Mahatma Gandhi—himself a Gujarati Baniya—helped elevate vegetarianism as a symbol of Indian nationalism, even though most Indians were non-vegetarian. Gandhi, in his auto-biographical account “The story of my experiments with truth” says “the basis of my vegetarianism is not physical, but moral. If anybody said that I should die if I did not take beef-tea or mutton, even under medical advice, I would prefer death. That is the basis of my vegetarianism.” He used this as a part of his political activism and pulled the Indian people together—amazing, given that most of them were carnivorous!

The modern reality

Today’s vegetarian map of India reflects this complex history:

High Vegetarian States (50%+):

- Rajasthan (75%)

- Haryana (70%)

- Punjab (67%)

- Gujarat (~65%)

Low Vegetarian States (<5%):

- Tamil Nadu (2.3%)

- Kerala (3%)

- West Bengal (1.4%)

- Andhra Pradesh (1.7%)

The national average of 29% vegetarian masks dramatic regional variations that trace back centuries.

The case of the sacred cow

As anyone who has been to India knows, the cow is a sacred animal protected by everyone. Eating beef is often taboo. So, a natural question that arises is “How did cows come to be sacred? And, when did this happen given that beef consumption was de rigueur in the early days of Hinduism?”

As it turns out, the transformation of the cow from food to sacred symbol follows the same timeline as the broader vegetarian revolution, but with an even more dramatic reversal. In Vedic times, cows were routinely sacrificed and eaten—the Rigveda mentions beef consumption over 50 times, and Vedic priests were among the biggest beef-eaters. Even while some cows were called “aghnya” (“that which may not be slaughtered”), this likely referred to dairy cows valuable for milk production rather than a religious prohibition.

The shift began during the Buddhist-Jain challenge of the 6th century BCE. Both religions promoted ahimsa, with Buddha specifically criticizing the massive beef consumption by the priestly class. But the real transformation came during what B.R. Ambedkar called the “Brahmin counter-revolution.” Faced with losing moral authority to Buddhism and Jainism, Brahmin priests strategically embraced cow protection as a way to reclaim spiritual leadership.

By 200 CE, animal slaughter became widely considered violent, and by 1000 CE, cow veneration and the beef taboo became mainstream Hindu tradition—but primarily among upper castes. The irony is striking: the very Brahmins who had been the greatest beef-eaters became the most ardent cow protectors, transforming a 1,500-year-old dietary practice into what many now consider an “ancient” Hindu tradition.

This wasn’t just religious—it was deeply political. As B.R. Ambedkar wrote in “The Untouchables” (1948): “The clue to the worship of the cow is to be found in the struggle between Buddhism and Brahmanism and the means adopted by Brahmanism to establish its supremacy over Buddhism.” According to Wendy Doniger, historian Romila Thapar describes how those who avoided beef may have regarded such restrictions as “a matter of status”—the higher the caste, the greater the food restrictions. Lower castes continued eating beef much longer, and even today, the beef taboo serves as a stark dividing line between touchable and untouchable communities. What appears as religious tradition is actually the result of competitive religious politics, social climbing, and centuries of cultural consolidation. And, I’d add, the simple economics of life.

Lessons from 3,000 years of food history

This journey through India’s vegetarian history reveals several profound insights:

- Cultural practices aren’t ancient traditions—they’re responses to specific historical circumstances

- Business needs often drive cultural change more than religious doctrine

- Geography and economics shape culture as much as religion and philosophy

- Regional variation is more significant than national generalizations

- Food choices reflect power structures and social hierarchies

My childhood assumption about Indian vegetarianism was both right and wrong. Right, because Malleswaram truly was a vegetarian stronghold. Wrong, because this represented one specific historical trajectory—that of Brahmin and merchant communities in certain regions—rather than a universal Indian tradition.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate the incredible diversity of Indian food culture and the complex interplay of factors that shape what we eat. It also reminds us that cultural practices we take for granted often have surprisingly recent origins and practical explanations.

The next time you see someone claim that “India is a vegetarian country,” you’ll know the real story: it’s a tale of religious innovation, business strategy, geographic adaptation, and social competition played out over millennia—resulting in one of the world’s most fascinating food cultures.